A new study points to why, and how, Io became the most volcanic body in the solar system.

Scientists with NASA’s Juno mission to Jupiter have discovered that a shallow global magma ocean in Io does not exist and measurements are consistent with Io having a mostly solid mantle. The finding solves a 44-year-old mystery about the subsurface origins of the moon’s most demonstrative geologic features.

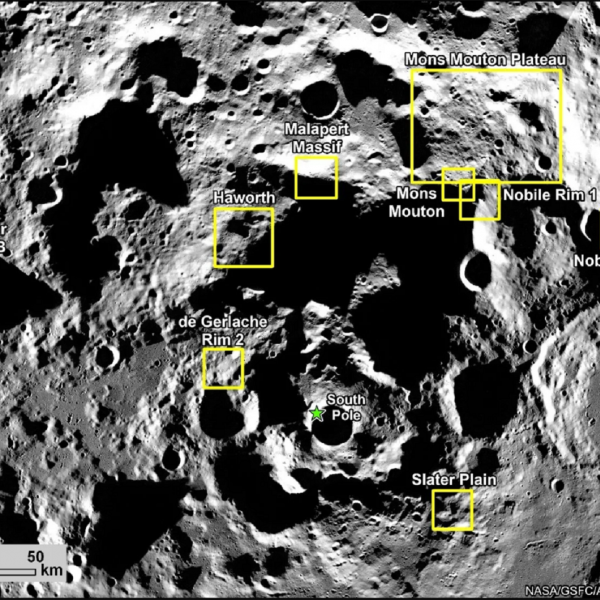

A paper on the source of Io’s volcanism was published in the journal Nature on Thursday, December 12. These findings, as well as other Io science results, were discussed during a media briefing in Washington at the American Geophysical Union’s annual meeting, the country’s largest gathering of Earth and space scientists. William McKinnon, the Clark Way Harrison Distinguished Professor in Arts & Sciences in the Department of Earth, Environmental, and Planetary Sciences, and a fellow in the McDonnell Center for the Space Sciences, is one of the authors of the paper entitled "Io’s tidal response precludes a shallow magma ocean."About the size of Earth’s Moon, Io is known as the most volcanically active body in our solar system. The moon is home to an estimated 400 volcanoes, which blast lava and plumes in seemingly continuous eruptions that contribute to the coating on its surface.

Although the moon was discovered by Galileo Galilei on Jan. 8, 1610, volcanic activity there wasn’t discovered until 1979, when imaging scientist Linda Morabito of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California first identified a volcanic plume in an image from the agency’s Voyager 1 spacecraft.

Read the complete NASA press release

Header image: The north polar region of Jupiter’s volcanic moon Io was captured by NASA’s Juno during the spacecraft’s 57th close pass of the gas giant on Dec. 30, 2023. Data from recent flybys is helping scientists understand Io’s interior.

Credit: Image data: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI/MSSS; Image processing by Gerald Eichstädt