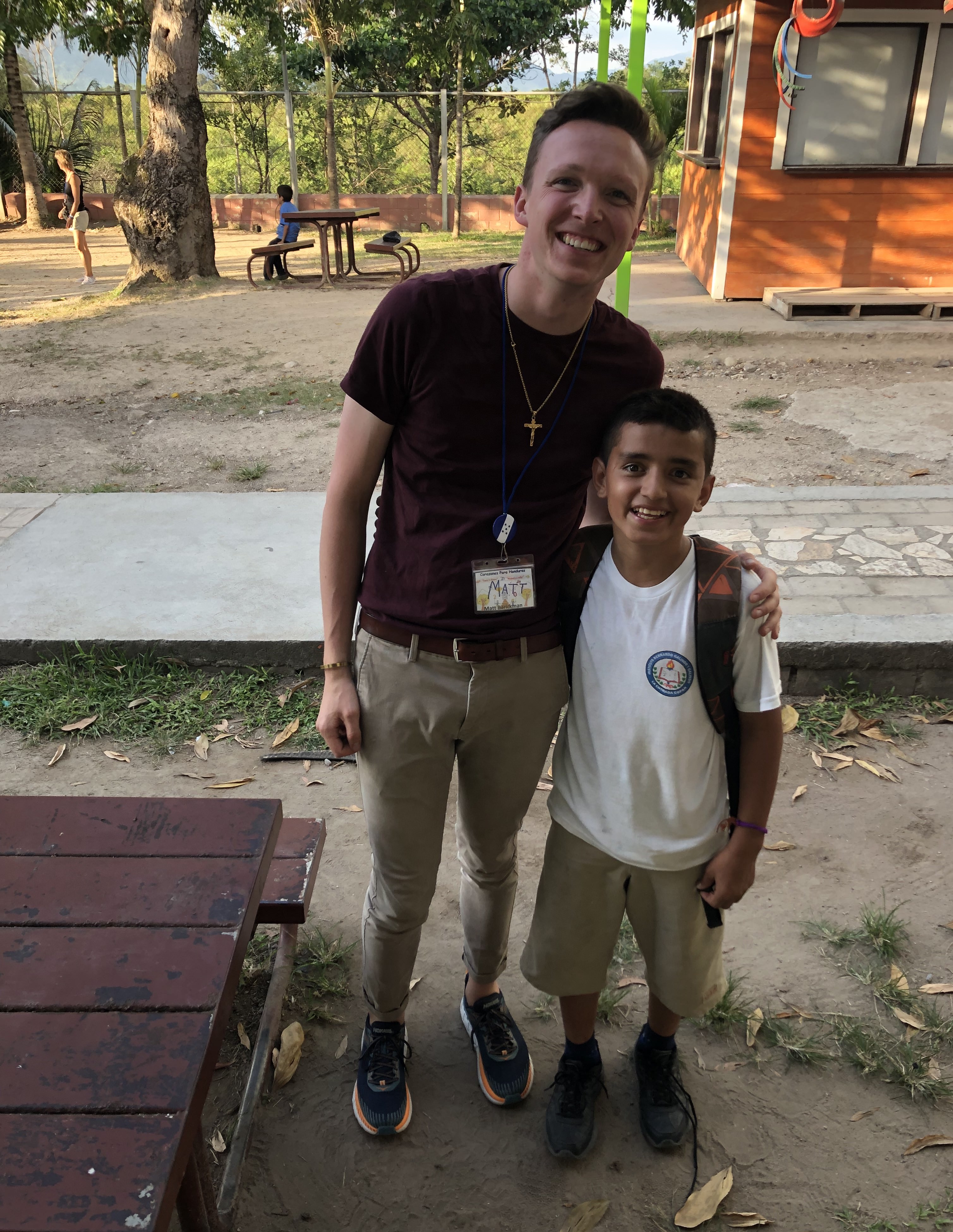

Mattison Barickman, a graduate student in the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, traveled to Honduras last summer to teach elementary school students Earth science. Here, Barickman describes his work, shares what drew him to the project, and offers advice for others considering similar outreach activities.

Tell me about the trip. Where did you go, and what were your goals?

I taught at a school called Hearts for Honduras, which is pretty remote in western Honduras. To get there, we flew into San Pedro Sula, which was not too long ago considered the crime capital of the world. We then drove a few hours west to a town called La Entrada. That’s “the entrance” in Spanish because it is so close to Guatemala. La Entrada has also been connected to the Central American drug trade.

We want to support an effort to change the dynamics of La Entrada from a place of dangerous instability and poverty to a community where everyone is involved with giving children a proper education, lifting each other up, and helping the less fortunate. As a developing nation, Honduras has stark income inequality, with very rich and very poor living side by side. Education is one way we can help bridge that gap.

What made you decide to participate in this project? Did you see a place for your skills as a geoscientist?

I had volunteered in Honduras before, first as a high school student in 2014 and then again on a teaching trip in 2015. I really got to know the teachers and students, which is important for building and maintaining a good relationship with the community.

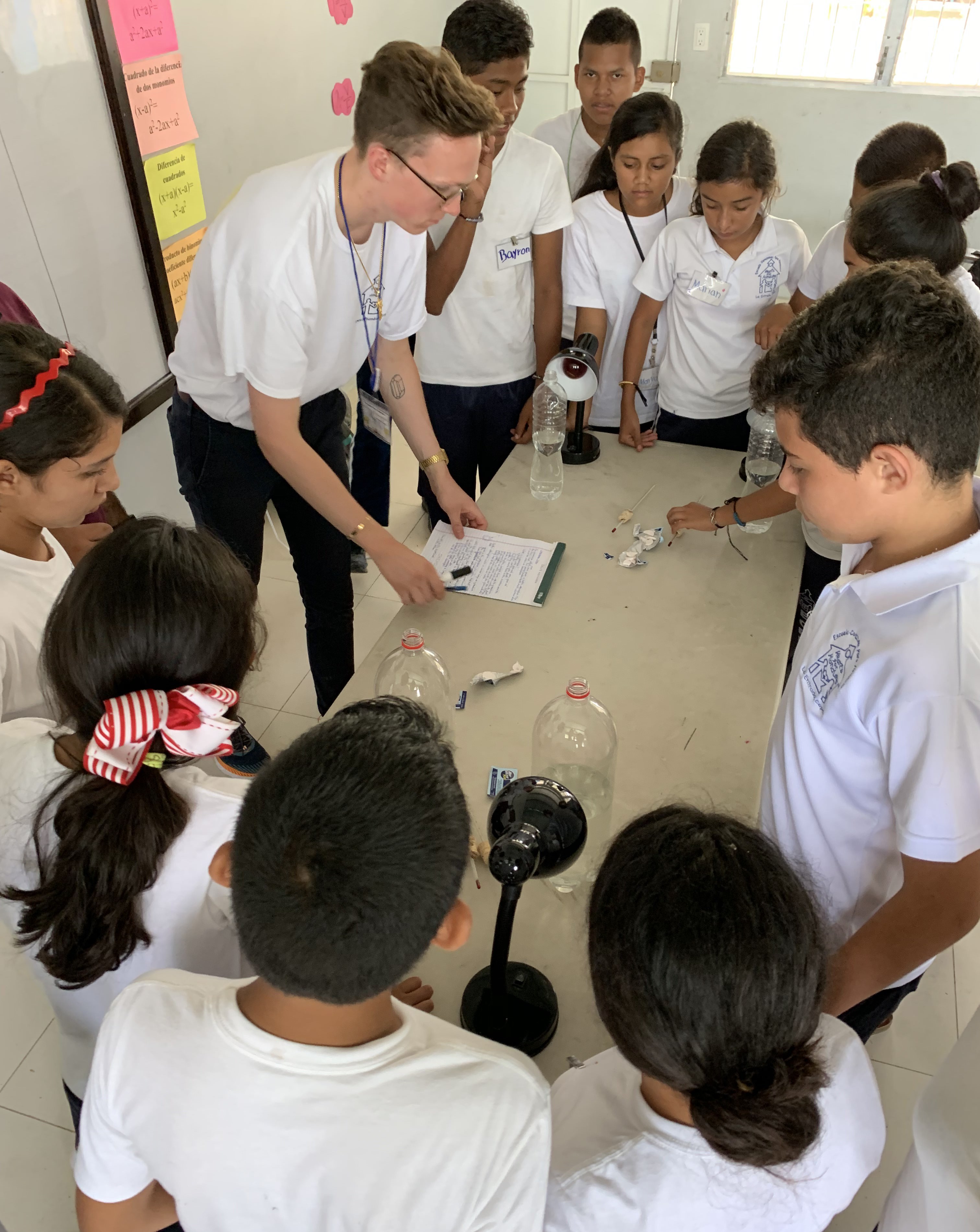

In 2019, I was given the opportunity to return, and I felt comfortable enough to do some teaching on my own. I definitely wanted Earth science to be my teaching focus. At that point, I had completed a degree in geological sciences, and I was in graduate school for Earth and planetary sciences, so I figured that was where I could best contribute. Specifically, I had noticed that their science classes didn’t have many hands-on activities. So every time I did an activity this year, it was an experiment or a lab activity where the kids could gain some first-hand experience doing science, making their own observations, and experiencing what it’s like to be a scientist. I’m not an expert educator, but I worked with their permanent science teacher to share my own skills.

What did you do on a day-to-day basis? Can you describe your experience working with teachers and students?

Before I even left WashU, I was gathering lab equipment, textbooks, and other donated resources. I knew materials were scarce where I would be working, so I looked for lessons and activities that could be completed using common items.

For example, in one activity I wanted to demonstrate the different types of plate boundaries, so we did “snack tectonics.” The activity only requires graham crackers, fruit roll ups, icing, water, and wax paper. The icing is the ductile asthenosphere, fruit roll ups are oceanic crust, and graham crackers represent continental crust. This was really fun for fourth-grade students because not only do they get to mimic different plate boundaries themselves, but they get to eat!

Another activity that turned out really well, but that I was nervous about, was based on Ray Arvidson’s volcanic hazards lab. This activity asked, if there was a volcanic eruption here, what would you do? The class divided into groups and presented their points in a debate. That’s where I was really worried—would an activity for college students work for fifth graders? But they got so into the activity! They were involved, outspoken, and very passionate about the exercise.

Connecting with students and letting them be the center of their own learning was the biggest lesson for me. They don’t want to hear me talk; they want to do science themselves. It was amazing to see students interacting with the world in their own way and making their own scientific observations.

Did you experience any challenges?

It’s important to challenge yourself about your motivations for doing something like this, to ask yourself, “Why am I going?” In 2014, I knew I wanted to contribute, but I didn’t have any specific idea of how I’d be giving back. This year, I had a clear purpose.

Another challenge is taking time away from graduate school. Even though this was only a two-week trip, it can be hard to schedule around conferences and other research obligations. Thankfully, my advisor, Rita Parai, is very understanding and supportive.

Do you have any advice for others considering a project like this?

Though this kind of trip isn’t a vacation, you are recharging in a different way. You’re giving back. There’s nothing like being the person who sparks an interest in science in a young student.

This is an area where I think science in general needs to come forward. As researchers, we make important discoveries and advance knowledge. That’s amazing, but we also need to ask ourselves how we can give back to our communities, how we can share science with other people. That outreach can take many different forms; it’s not all K-12, and it doesn’t necessarily require lots of extra time or training. For example, I’ve participated in Skype a Scientist. Here at WashU, we have the Young Scientist Program as well.

Also, set realistic expectations. Not everything will go perfectly, and that’s ok. I had an experiment fail, but it turned into an opportunity to talk about the scientific method and reproducibility. What do you do when an experiment fails? Try again.

Acknowledgements

Barickman would like to thank Hugh Chou, who donated a projector, and Michael Wysession, who donated textbooks in Spanish. Barickman also acknowledges his use of the Science Education Resource Center at Carleton College as an educational resource.