Zoltán Váci is a geologist whose interests lie in space. He is particularly fascinated by the first few million years of Solar System formation and the processes that transformed primordial gas and dust into pebbles, cobbles, boulder-sized material, and eventually into planets. Through his research, he aims to answer fundamental questions about the composition of the Universe, the structure of the Solar System, and the processes involved in planet formation.

Váci’s work delves into the intricacies of celestial body formation, focusing on both large terrestrial planets similar to Earth and Mars, and smaller objects known as planetesimals. These planetesimals, considered the building blocks of larger worlds, originated from dust particles and gases in the protoplanetary disk that surrounded the young Sun. Through collisions and accretion, these dust particles gradually accumulated into larger and more complex structures.

His research involves the detailed analysis of meteorites, focusing on those potentially originating from planetesimals whose sizes range from a few kilometers to moon-sized or larger. Despite their rarity in the meteoritic record, these rocks are crucial for understanding early planetary processes. Determining whether a meteorite originated from a planetesimal involves a comprehensive analysis of its physical, chemical, and isotopic characteristics. These data are then integrated to answer questions relating to the size of the parent body and the age of its igneous differentiation.

Váci’s investigations while at WashU have focused on planetary volcanism, as meteorites from planetesimals are typically achondrites - igneous rocks that are products of planetary differentiation. This process causes materials to separate into distinct core, crust, and mantle layers, not unlike the processes that occur underneath terrestrial volcanoes like Mount St. Helens.

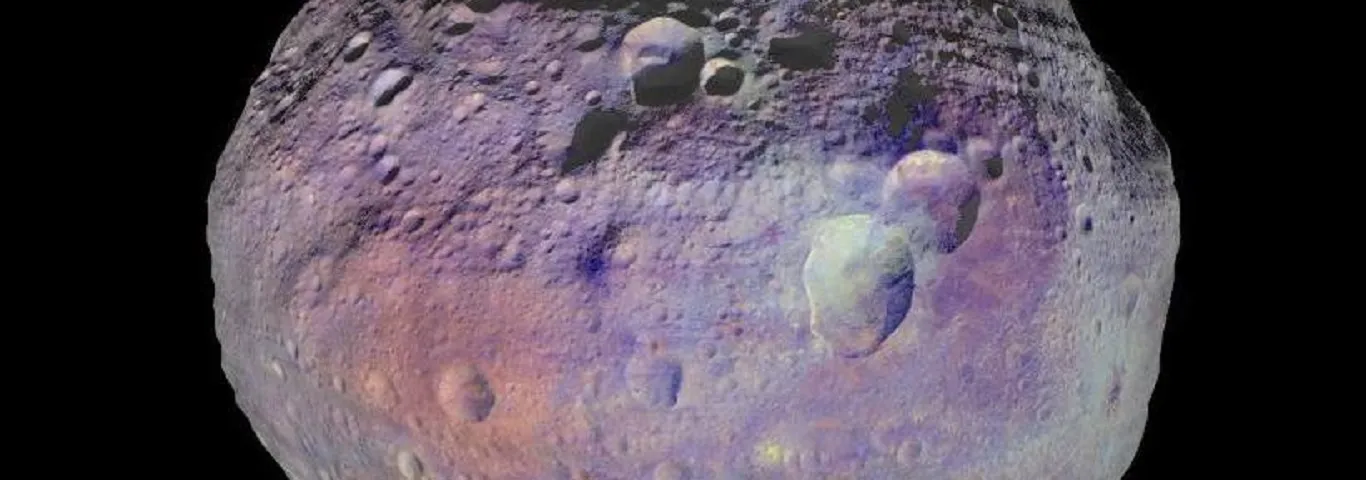

Recently, Váci published an article in Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta that explores these processes in a planetesimal potentially linked to the asteroid Vesta, one of the largest objects in the asteroid belt, located between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter. Studying these meteorites offers valuable insights into the evolutionary history of these early forming planets and planetesimals, helping us understand the mechanisms that drove their formation and development.

Váci was the first McDonnell Center postdoctoral research associate appointed since Brad Jolliff assumed the role of Director of the McDonnell Center for the Space Sciences (MCSS). During his tenure at WashU, Váci has engaged in multiple collaborative projects with MCSS fellows. He has worked with Michael Krawczynski on experimental petrology, measured potassium isotopes in meteorites in Kun Wang's lab, and contributed to a grant proposal for an Io sample return mission with Ryan Ogliore. In his third year, he collaborated with David Fike's research group on a Department of Energy project led by Young-Shin Jun, a professor in Energy, Environmental and Chemical Engineering. Krawczynski, Wang, and Fike are professors in the Department of Earth, Environmental, and Planetary Sciences, while Ogliore is a professor in the Department of Physics.

According to Krawczynski, "Zoltán has that rare quality to make an instant positive impact when joining new research groups with his infectious scientific curiosity and innate talent for sparking collaborations between analytical and experimental research groups."

Looking ahead, Váci will be taking a position at Charles University in Prague, Czechia, as a postdoctoral fellow working on a large European geohazards grant. There, he will continue his work as an experimental petrologist, switching field area from outer space to terrestrial volcanoes. As the same thermodynamic principles govern magmatism on Earth and on small bodies, Váci hopes to continue his contributions to space science research by studying the formation of shallow magma bodies on this planet.

Reflecting on his experience, Váci said, “MCSS consists of a huge concentration of expertise and instruments. There are a lot of brilliant people to work with and a lot of world-class instruments. For me, it's like a playground. Who do I want to work with? What do I want to do next? It has been great to connect with all these different people across many subfields and develop my long-term research agenda. In short, working at MCSS has helped me become a better scientist.”